The culture of Romania

Postat 03-01-2021

The culture of Romania is a unique culture, which is the product of its geography and its distinct historical evolution. It is theorized that Romanians, (Proto-Romanians, including Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians, and Istro-Romanians) are the combination of descendants of Roman colonists and people indigenous to the region who were Romanized. The Dacian people, one of the major indigenous peoples of Central and Southeast Europe are one of the predecessors of the Proto-Romanians.

Introduction to Romanian Culture

The culture of Romania is a unique culture, which is the product of its geography and its distinct historical evolution. It is theorized and speculated that Romanians, (Proto-Romanians, including Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians, and Istro-Romanians) are the combination of descendants of Roman colonists and people indigenous to the region who were Romanized. The Dacian people, one of the major indigenous peoples of Central and Southeast Europe are one of the predecessors of the Proto-Romanians. It is believed that a mixture of Romans, Dacians, Slavs, and Illyrians are the predecessors of the Romanians, Aromanians (Vlachs), Megleno-Romanians, and Istro-Romanians. Romanian culture shares some similarities as well with other ancient cultures even outside of the Balkans, such as that of the Armenians.

During late Antiquity and Middle Ages, the major influences came from the Slavic peoples who migrated and settled south of the Danube; from medieval Greeks, and the Byzantine Empire; from the Hungarians; from the germans, especially saxonian germans and from several other neighboring peoples. Modern Romanian culture emerged and developed with many other influences as well, partially that of Central and Western Europe.

Romania's history has been full of rebounds: the culturally productive epochs were those of stability, when the people proved quite an impressive resourcefulness in making up for less propitious periods and were able to rejoin the mainstream of European culture. This stands true for the years after the Phanariote-Ottoman period, at the beginning of the 19th century, when Romanians had a favourable historical context and Romania started to become westernized, mainly with French influences, which they pursued steadily and at a very fast pace. From the end of the 18th century, the sons of the upper classes started having their education in Paris, and French became (and was until the communist years) a genuine second language of culture for Romanians. The modeling role of France especially in the fields of political ideas, administration and law, as well as in literature was paralleled, from the mid-19th century down to World War I, by German culture as well, which also triggered constant relationships with the German world not only at a cultural level but in daily life as well. With the arrival of Soviet Communism in the area, Romania quickly adopted many Slavic influences, and Russian was also a widely taught in the country during Romania's "socialist" years.

The Romanian Culture in the Middle Age

The Middle Ages

Until the 14th century, small states (Romanian: voievodate) were spread across the territory of Transylvania, Wallachia, and Moldova. The medieval principalities Wallachia and Moldavia arose around that time in the area on the southern and eastern sides of the Carpathian Mountains.

Wallachia and Moldavia were both situated on important commercial routes often crossed by Polish, Saxon, Greek, Armenian, Genovese, and Venetian merchants, connecting them well to the evolving culture of medieval Europe. Grigore Ureche's chronicle, "Letopiseţul Ţărîi Moldovei" (The Chronicles of the land of Moldavia), covering the period from 1359 to 1594, is a very important source of information about life, events, and personalities in Moldavia. It is among the first non-religious Romanian literary texts; due to its size and the information that it contains it is, probably, the most important Romanian document from the 17th century.

The first printed book, a prayer book in Slavonic, was produced in Wallachia in 1508 and the first book in Romanian, a catechism, was printed in Transylvania, in 1544.

At the end of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th century, European humanism influenced the works of Miron Costin and Ion Neculce, the Moldavian chroniclers who continued Ureche's work. Constantin Brâncoveanu, prince of Wallachia, was a great patron of the arts and was a local Renaissance figure. During Şerban Cantacuzino's reign the monks at the monastery of Snagov, near Bucharest published in 1688 the first translated and printed Romanian Bible (Biblia de la Bucureşti - The Bucharest Bible). The first successful attempts at written Romanian-language poetry were made in 1673 when Dosoftei, a Moldavian metropolitan in Iaşi, published a Romanian metrical psalter.

Dimitrie Cantemir, a Moldavian prince, was an important personality of the medieval period in Moldavia. His interests included philosophy, history, music, linguistics, ethnography, and geography, and the most important works containing information about the Romanian regions were Descriptio Moldaviae published in 1769 and Hronicul vechimii a romano-moldo-valahilor (roughly, Chronicle of the durability of Romans-Moldavians-Wallachians), the first critical history of Romania. His works were also known in western Europe, as he authored writings in Latin: Descriptio Moldaviae (commissioned by the Academy of Berlin, the member of which he became in 1714) and Incrementa atque decrementa aulae othomanicae, which was printed in English in 1734-1735 (second edition in 1756), in French (1743) and German (1745); the latter was a major reference work in European science and culture until the 19th century.

The Classical Age of the Romanian Culture

In Transylvania, although they formed the majority of the population, Romanians were merely seen as a "tolerated nation" by the Austrian leadership of the province and were not proportionally represented in political life and the Transylvanian Parliament. At the end of the 18th century, an emancipation movement known as the Transylvanian School (Şcoala Ardeleană) formed, which tried to emphasize that the Romanian people were of Roman origin and also adopted the modern Latin-based Romanian alphabet (which eventually supplanted an earlier Cyrillic script). It also accepted the leadership of the pope over the Romanian church of Transylvania, thus forming the Romanian Greek-Catholic Church.

In 1791, they issued a petition to Emperor Leopold II of Austria, named Supplex Libellus Valachorum based on the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, demanding equal political rights with the other ethnicities for the Romanians in Transylvania. This movement, however, leaned more towards westernization in general, when in fact the origin of the Romanian people is not only from the peoples of the former Roman Empire, but also from the ancient Dacians, predating the arrival of the Romans, not to mention that from around the 1600s to the 1800s Romanian culture was heavily influenced by Eastern influences as emphasized through the Ottomans, and the Phanariotes.

The end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century was marked in Wallachia and Moldavia by the reigns of Phanariote Princes; thus the two principalities were heavily influenced by the Greek world. Greek schools appeared in the principalities and in 1818 the first Romanian School was founded in Bucharest by Gheorghe Lazăr and Ion Heliade Rădulescu. Anton Pann was a successful novelist, Ienăchiţă Văcărescu wrote the first Romanian grammar, and his nephew Iancu Văcărescu is considered to be the first important Romanian poet. In 1821 an uprising in Wallachia (a region of Romania) took place against Ottoman rule. This uprising was led by the Romanian revolutionary and militia leader Tudor Vladimirescu.

The revolutionary year 1848 had its echoes in the Romanian principalities and in Transylvania, and a new elite from the middle of the 19th century emerged from the revolutions: Mihail Kogălniceanu (writer, politician and the first prime minister of Romania), Vasile Alecsandri (politician, playwright, and poet), Andrei Mureşanu (publicist and the writer of the current Romanian National Anthem) and Nicolae Bălcescu (historian, writer and revolutionary).

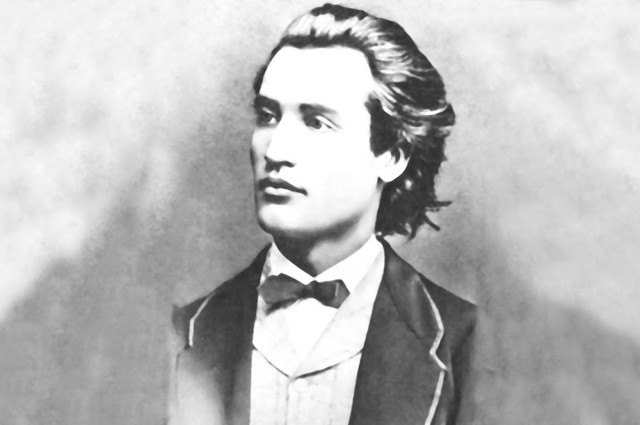

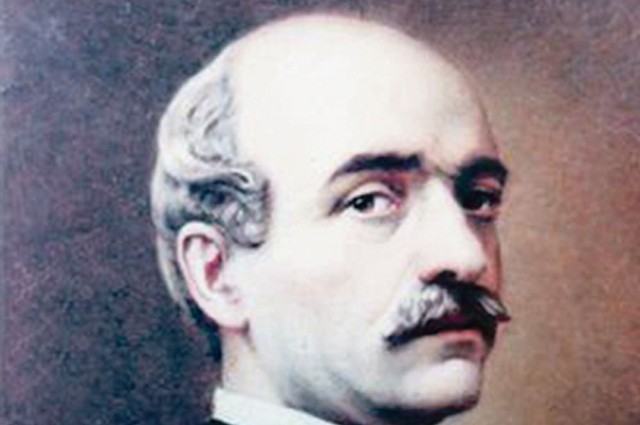

The union between Wallachia and Moldavia in 1859 brought a growing consolidation of Romanian life and culture. Universities were opened in Iaşi and in Bucharest and the number of new cultural establishments grew significantly. The new prince from 1866 and then King of Romania, Carol I was a devoted king, and he and his wife Elisabeth were among the main patrons of arts. Of great impact in Romanian literature was the literary circle Junimea, founded by a group of people around the literary critic Titu Maiorescu in 1863. It published its cultural journal „Convorbiri Literare” where, among others, Mihai Eminescu, Romania's greatest poet, Ion Creangă, a storyteller of genius, and Ion Luca Caragiale, novelist and Romania's greatest playwright published most of their works. During the same period, Nicolae Grigorescu and Ştefan Luchian founded modern Romanian painting; composer Ciprian Porumbescu was also from this time.

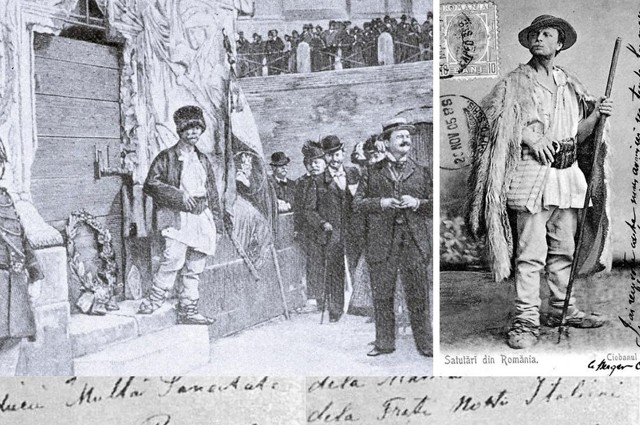

In Transylvania, the emancipation movement became better organized and in 1861 an important cultural organization ASTRA (The Transylvanian Association for Romanian Literature and the Culture of the Romanian People) was founded in Sibiu under the close supervision of the Romanian Orthodox Metropolitan Andrei Şaguna. It helped publish a great number of Romanian language books and newspapers, and between 1898 and 1904 it published a Romanian Encyclopedia. Among the greatest personalities from this period are the novelist and publicist Ioan Slavici, the prose writer Panait Istrati, the poet and writer Barbu Ştefănescu Delavrancea, the poet and publicist George Coşbuc, the poet Ştefan Octavian Iosif, the historian and founder of Romanian press in Transylvania George Bariţiu and Badea Cârţan, a simple peasant shepherd from Southern Transylvania who, through his actions became a symbol of the emancipation movement.

Badea Cârțan (roughly: Brother Cârțan – the common nickname of Gheorghe Cârțan; 24 January 1849 – 7 August 1911) was a self-taught ethnic Romanian shepherd who fought for the independence of the Romanians of Transylvania (then under Hungarian rule inside Austria-Hungary), distributing Romanian-language books that he secretly brought from Romania to their villages. In all he smuggled some 200,000 books for pupils, priests, teachers, and peasants; he used several routes to pass through the Făgăraş Mountains.

He was born in Opra Kertsesora, during the Hungarian occupation of Transylvania, (Romanian: Oprea-Cârțișoara, today part of Cârțișoara, Romania), the second child of poor peasants (Nicolae and Ludovica) who was former serfs, and he spent his childhood tending sheep at the edge of his village. In between his later brushes with fame, he would always return to this activity. He became the head of his family on 2 October 1865 with the death of his father.

Cârţan an first crossed the mountains into the Romanian Old Kingdom, founded at 1859, with his sheep and a friend at the age of 18, and it was at that time that his interest in Romanian national unity became powerful. In 1877 he enrolled as a volunteer in the Romanian War of Independence, serving until 1881. In 1895 he traveled to Vác and Szeged to visit imprisoned Romanians, including the signatories of the Transylvanian Memorandum. Badea Cârțan himself was arrested twice: once because he asked the Emperor-King Franz Joseph at Vienna for Transylvania's self-determination, and once because he asked the authorities for permission to sell Romanian books.

Cârțan made a journey on foot to Rome, and when he arrived at the city's edge after 45 days, said, "Bine te-am găsit, maica Roma" ("Pleased to meet you, mother Rome"). He wished to see Trajan's Column with his own eyes, as well as other evidence of the Latin origin of the Romanian people. After pouring Romanian soil and wheat at the column's base, he wrapped himself in a peasant's coat (cojoc) and fell asleep at the column's base. The next day he was awakened by a policeman who shouted in amazement, "A Dacian has fallen off the column!", as Cârţan was dressed just like the Dacians carved into the column; the event was reported in Roman newspapers and Duiliu Zamfirescu, Romanian representative in Italy, showed him around the city and introduced him to its important personalities. This January-February 1896 trip was but one of three visits to Rome; on his last, in October 1899, on the occasion of a meeting of the International Congress of Orientalists, he laid a wreath at the column's base.

Cârțan also visited France, Spain, Belgium, Switzerland, Germany, Egypt, and Jerusalem.

He was buried in Sinaia, on soil belonging to the Kingdom of Romania (Transylvania still being seven years away from the declaration of the union with Romania); on the stone cross atop his grave is inscribed the phrase: "Aici doarme Badea Cârțan visând întregirea neamului său" ("Here lies Badea Cârțan dreaming of the unity of his people").

The Lake

Water lilies load all over

The blue lake amid the woods,

That imparts, while in white circles

Startling, to a boat its moods.

And along the strands I'm passing

Listening, waiting, in unrest,

That she from the reeds may issue

And fall, gently, on my breast;

That we may jump in the little

Boat, while water's voices whelm

All our feelings; that enchanted

I may drop my oars and helm;

That all charmed we may be floating

While moon's kindly light surrounds

Us, winds cause the reeds to rustle

And the waving water sounds.

But she does not come; abandoned,

Vainly I endure and sigh

Lonely, as the water lilies

On the blue lake ever lie.

(1876, Translated by Dimitrie Cuclin)

A Dacian's Prayer

When death did not exist, nor yet eternity,

Before the seed of life had first set living free,

When yesterday was nothing, and time had not begun,

And one included all things, and all was less than one,

When sun and moon and sky, the stars, the spinning earth

Were still part of the things that had not come to birth,

And You quite lonely stood... I ask myself with awe,

Who is this mighty God we bow ourselves before.

Ere yet the Gods existed already He was God

And out of endless water with fire the lightning shed;

He gave the Gods their reson, and joy to earth did bring,

He brought to man forgiveness, and set salvation's spring

Lift up your hearts in worship, a song of praise enfreeing,

He is the death of dying, the primal birth of being.

To him I owe my eyes that I can see the dawn,

To him I owe my heart wherein is pity born;

Whene'er I hear the tempest, I hear him pass along

Midst multitude of voices raised in a holy song;

And yet of his great mercy I beg still one behest:

That I at last be taken to his eternal rest.

Be curses on the fellow who would my praise acclaim,

But blessings upon him who does my soul defame;

Believe no matter whom who slanders my renown,

Give power to the arm that lifts to strike me down;

Let him upon the earth above all others loom

Who steals away the stone that lies upon my tomb.

Hunted by humanity, let me my whole life fly

Until I feel from weeping my very eyes are dry;

Let everyone detest me no matter where I go,

Until from persecution myself I do not know;

Let misery and horror my heart transform to stone,

That I may hate my mother, in whose love I have grown;

Till hating and deceiving for me with love will vie,

And I forget my suffering, and learn at last to die.

Dishonoured let me perish, an outcast among men;

My body less than worthy to block the gutter then,

And may, o God of mercy, a crown of diamonds wear

The one who gives my heart the hungry dogs to tear,

While for the one who in my face does callous fling a clod

In your eternal kingdom reserve a place, o God.

Thus only, gracious Father, can I requitance give

That you from your great bounty vouched me the joy to live;

To gain eternal blessings my head I do not bow,

But rather ask that you in hating compassion show.

Till comes at last the evening, your breath will mine efface,

And into endless nothing I go, and leave no trace.

(1879, Translated by Corneliu M. Popescu)

Ode (in ancient meter)

Hardly had I thought I should learn to perish;

Ever young, enwrapped in my robe I wandered,

Raising dreamy eyes to the star styled often

Solitude's symbol.

All at once, however, you crossed my pathway -

Suffering - you, painfully sweet, yet torture...

To the lees I drank the delight of dying -

Pitiless torment.

Sadly racked, I'm burning alive like Nessus,

Or like Hercules by his garment poisoned;

Nor can I extinguish my flames with every

Billow of oceans.

By my own illusion consumed I'm wailing

On my own grim pyre in flames I'm melting...

Can I hope to rise again like the Phoenix

Bird from the ashes?

May all tempting eyes vanish from my pathway

Come back to my breast, you indifferent sorrow!

So that I may quietly die, restore me

To my own being!

(1883, Translated by Andrei Bantas)

We want land !

I'm hungry, naked, homeless, through,

Because of loads I had to carry;

You've spat on me, and hit me - marry,

A dog I've been to you !

Vile lord, whom winds brought to this land,

If hell itself gives you free hand

To tread us down and make us bleed,

We will endure both load and need,

The plough and harness yet take heed,

We ask for land!

Whene'er you see a crust of bread,

Though brown and stale, we see's no more;

You drag our sons to ruthless war,

Our daughters to your bed.

You curse what we hold dear and grand,

Faith and compassion you have banned;

Our children starve with want and chill

And we go mad with pity, still

We'd bear the grinding of your mill,

Had we but land !

You've turned into a field of corn

The village graveyard, and we plough

And dig out bones and weep and mourn

Oh, had we ne'er been born !

For those are bones of our own bone,

But you don't care, o hearts of stone !

Out of our house you drive us now,

And dig our dead out of their grave;

A silent corner of their own

The land we crave !

Besides, we want to know for sure

That we, too, shall together lie,

That on the day on which we die,

You will not mock the poor.

The orphans, those to us so dear,

Who o'er a grave would shed a tear,

Won't know the ditches where we rot;

We've been denied a burial plot

Though we are Christians, are we not ?

We ask for land, d'you hear ?

Nor have we time to say a prayer,

For time is in your power too;

A soul is all we have, and you

Much you do care !

You've sworn to rob us of the right

To tell our grievances outright;

You give us torture when we shout,

Unheard-of torture, chain and clout

And lead when, dead tired, we cry out:

For land we'll fight !

What is it you've here buried ? say !

Corn ? maize ? We have forbears and mothers,

We, fathers, sisters dear and brothers !

Unwished - for guests, away !

Our land is holy, rich and brave,

It is our cradle and our grave;

We have defended it with sweat

And blood, and bitter tears have wet

Each palm of it - so, don't forget:

'Tis land we crave !

We can no more endure the goads,

No more the hunger, the disasters

That follow on the heels of masters

Picked from the roads !

God grant that we shall not demand

Your hated blood instead of land !

When hunger will untie our ties

And poverty will make us rise.

E'en in your grave we will chastise

You and your band !

Three, mighty God, all three!

He had three sons and they, all three,

When called, for the encampment left;

So the poor father was bereft

Of rest and peace, for war, thought he.

Is hard - one has no time to feel

That one has ceased to be.

And many months went in and out,

And rife with tidings was the world:

No more were Turkish flags unfurled,

The Moslems had been put to rout,

For the unscarred Romanian lads

Full well had fought throughout.

The papers wrote that all the men

That had been called the spring before

Were due to quit the site of war;

So to the village came again

Now one, and now another yet

Of those who had left then.

But they were long in coming, they.

He wept - he thought how they would meet,

So at the gate or in the street

He scrutinized the roads all day,

And they came not. And fear was born

And lengthened the delay.

His ardent hope waned more and more

And ever bleaker grew his fear;

And though he questioned far and near,

All shrugged their shoulders as before;

At last, then, he went to the barracks

To learn what was in store.

The corporal met him. "Sir, my son.

My Radu, well - how does he fare ?"

He did for all his children care,

But Radu was the dearest one.

"He's dead. In the first ranks, at Plevna

He fell. And well he's done !"

Poor man... That Radu was in dust

He had long felt, and felt past cure;

But now, when he did know for sure,

He stood bewildered and nonplussed.

Dead Radu ? What ? The news exceeded

All human sense and trust.

Be curst, o, fiendish arm and man !

"And how is George ?" "Sir, I'm afraid

Under a cross he has been laid,

Breast-smitten by a yataghan."

"And my poor Mircea ?" "Mircea, too,

Died somewhere near Smirdan."

He said no word - dumb with the doom,

With forehead bent, like, on the cross,

A Christ, he looked, all at a loss

At the mute flooring of the room.

He seemed he saw in front of him

Three corpses in a tomb.

With feeble gait and dizzy eyes

He walks into the open air;

While groaning, stumbling on the stair,

He calls his boys by name and cries

And fumbling for some wall around

To stand upright he tries.

The blow he hardly can withstand;

He does not know if he is dead

Or still alive; he rests his head

Upon a bank of burning sand;

His long, emaciated face

He buries in his hand.

And so the man sat woe-begone.

It was midsummer and mid-day;

Yet soon the sun faded away

And lastly it was set and gone;

The human wreck would never budge;

He just stood on and on.

Past him, men, women walked care-free,

Cabs on the highroad rumbled by,

Past marched the soldiers with steps high,

And then, the moment he could see,

He pressed his temples with his fists:

"Three, mighty God, all three !";

Decebal to his people

This life is a lost boon if you

Don't live it as you wanted to!

Much would a warlike, ruthless foe

Enslave us all! Our birth, we know,

Was woe enough; would you get through

Another dreadful woe?

Death, even for a godlike scion,

Is a hard law, as hard as iron!

It is all one to breathe one's last

A lad or an old man bypast,

But not the same to die a lion

Or a poor dog chained fast.

What if you fight in the first line,

What if by great exploits you shine?

A grumbler cannot better be

Than those who fear to fight and flee!

To murmur is to have no spine

And make a bootless plea!

Like dead men, cowards will keep still!

The living - let them laugh at will!

The really good ones laugh and die.

Hold, therefore, heroes, your brows high

And let your lusty cheering fill

Both hell and earth and sky!

Blood may in floods and torrents flow,

The arm assail with spear and blow,

When the fierce enemies are dead!

Well, you may think yourself Godhead,

When you but laugh at what the foe

Does more than all else dread.

They're Romans, we know that. So what?

Where they not Romans but our god,

Zamolxes, with his creatures, still

We would, sure, ask them what they will -

They won't get of our land a jot:

They have their skies to fill!

Now, men, to sword and shield and horn!

'Twas bad enough that we were born;

But he is free to go whose fright

Makes him too dastardly to fight,

And if there is someone foresworn,

Let him avoid our sight!

What I have told you is enow!

You swore on shields your oath of love

For Dacia! Might resides in you

And in the gods! But, heroes, know

That they, the gods, are far above,

Our foes - at a stone's throw!

The Golden Age of the Romanian Culture

The first half of the 20th century is regarded by many as the golden age of Romanian culture and it is the period when it reached its main level of international affirmation and a strong connection to the European cultural trends. The most important artist who had a great influence on the world culture was the sculptor Constantin Brâncuși (1876–1957), a central figure of the modern movement and a pioneer of abstraction, an innovator of world sculpture by immersion in the primordial sources of folk creation.

The relationship between traditional and Western European trends was a subject of heated polemics and outstanding personalities sustained the debates. The playwright, expressionist poet, and philosopher Lucian Blaga can be cited as a member of the traditionalist group and the literary critic founder of the literary circle and cultural journal Sburătorul, Eugen Lovinescu, represents the so-called Westernizing group, which sought to bring Romanian culture closer to Western European culture. Also, George Călinescu was a more complex writer who, among different literary creations, produced the monumental "History of the Romanian literature, from its origins till present day".

The beginning of the 20th century was also a prolific period for Romanian prose, with personalities such as the novelist Liviu Rebreanu, who described the struggles in the traditional society and the horrors of war, Mihail Sadoveanu, a writer of novels of epic proportions with inspiration from the medieval history of Moldavia, and Camil Petrescu, a more modern writer distinguishing himself through his analytical prose writing. In dramaturgy, Mihail Sebastian was an influential writer, and as the number of theaters grew also did the number of actors, Lucia Sturdza Bulandra being an actress representative of this period.

Alongside the prominent poet George Topîrceanu, a poet of equal importance was Tudor Arghezi who was the first to revolutionize poetry in the last 50 years. One should not neglect the poems of George Bacovia a symbolist poet of neurosis and despair and those of Ion Barbu a brilliant mathematician who wrote a series of very successful cryptic poems. Tristan Tzara and Marcel Janco, founders of the Dadaist movement, were also of Romanian origin.

Also during the golden age came the epoch of Romanian philosophy with such figures as Mircea Vulcănescu, Dimitrie Gusti, Alexandru Dragomir, and Vasile Conta. The period was dominated by the overwhelming personality of the historian and politician Nicolae Iorga who, during his lifetime published over 1,250 books and wrote more than 25,000 articles. In music, the composers George Enescu and Constantin Dimitrescu and the pianist Dinu Lipatti became world-famous. The number of important Romanian painters also grew, and the most significant ones were: Nicolae Tonitza, Camil Ressu, Francisc Şirato, Ignat Bednarik, Lucian Grigorescu, and Theodor Pallady. In medicine, a great contribution to human society was the discovery of insulin by the Romanian scientist Nicolae Paulescu. Gheorghe Marinescu was an important neurologist and Victor Babeş was one of the earliest bacteriologists. In mathematics Gheorghe Ţiţeica was one of Romania's greatest mathematicians, and also an important personality was the mathematician/poet Dan Barbilian.

Post World War II Period of The Romanian Culture

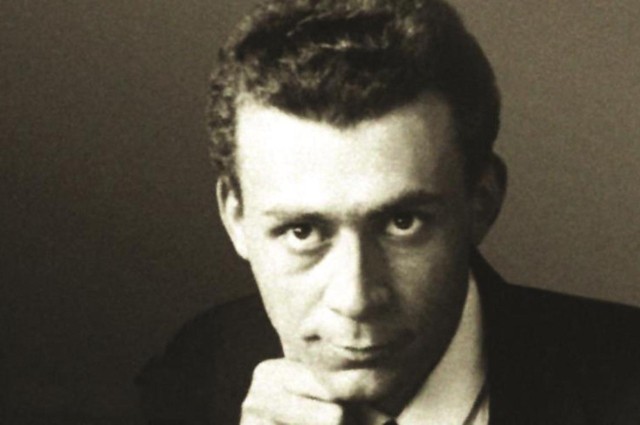

In Romania, the so-called communist regime imposed heavy censorship on almost all elements of life and they used the cultural world as a means to better control the population. The freedom of expression was constantly restricted in various ways: the Sovietization period was an attempt at building up a new cultural identity on the basis of socialist realism and lending legitimacy to the new order by rejecting traditional values. Two currents appeared: one that glorified the regime and another that tried to avoid censorship. The first is probably of no lasting cultural value, but the second managed to create valuable works, successfully avoiding censorship and being very well received by the general public. From this period the most outstanding personalities are those of the writer Marin Preda, the poets Nichita Stănescu and Marin Sorescu, and the literary critics Nicolae Manolescu and Eugen Simion. Most dissidents who chose not to emigrate lived a life closely watched by the regime, either in "house arrest" or in "forced domicile"; some chose to retreat to remote monasteries. Most of their work was published after the 1989 Revolution. Among the most notable examples are the philosophers Constantin Noica, Petre Ţuţea, and Nicolae Steinhardt.

There was a chasm between the official, communist culture, and genuine culture. On the one hand, against the authorities' intentions, the outstanding works were perceived as a realm of moral truths, and the significant representatives of genuine cultural achievement were held in very high esteem by the public opinion. On the other hand, the slogans disseminated nationwide through the forms of official culture helped spread simplistic views, which were relatively successful among some ranks of the population. The tension between these two directions can still be perceived at the level of society as a whole.

A Poem

Tell me, if I caught you one day

and kissed the sole of your foot,

wouldn't you limp a little then,

afraid to crush my kiss?...

Burned forest

Black snow was falling. The tree line

shone when I turned to see -

I had wondered long and silent,

alone, trailing memory behind me.

And it seemed the stars, fixed as they were,

ground their teeth, a stiffened nexus,

an infernal machine, tolling

the halted hours of conciousness.

Then, a thick silence descends,

and my every gesture

leaves a comet tail in the heavens.

And I hear evey glance I cast

as it echoes against

some tree.

Child, what were you seeking there,

with your gangly arms and pointed shoulders

on which the wings were barely dry -

black snow drifting in the evening sky.

A horizon howling, far from view,

darting its tongues and anthracite,

dragged me forever down the mute row,

my body, half naked, sliding from sight.

In distances of smoke the town afire,

blazing beneath the planes, a frigid pyre.

We two, forest, what did we do?

Why did they burn you, forest, in a toga of ash -

and the moon no longer passes over you?

From the book "Bas-Relief with Heroes"

english translation by Thomas Carlson and Vasile Poenaru.

Culture inside communist Romania

A strong editorial activity took place during the Communist regime. With the purpose of educating the large masses of peoples, a huge number of books were published. Large-scale editing houses such as Cartea Românească, Editura Eminescu, and others appeared, which published huge collections of books, such as the Biblioteca pentru Toţi ("The Library for Everyone") with over 5,000 titles. Generally, a book was never published in an edition of fewer than 50,000 copies. Libraries appeared in every village and almost all were kept up to date with the newest books published. Also, due to low prices, almost everyone could afford to have their own collection of books at home. The negative part was that all the books were heavily censored. Also, due to rationing in every aspect of life, the quality of the printing and the paper also was very low, and the books, therefore, degraded easily.

During this period, there was a significant increase in the number of theatres, as they appeared even in the smallest towns. Many new establishments were built and in the big cities, they became important landmarks, such as the building of the National Theatre of Bucharest, situated right in the middle of the city, immediately adjacent to Romania's kilometer zero. In the smaller towns, there existed the so-called "Worker's Theatre", a semi-professional institution. Partly due to the lack of other entertainment venues, the theatre was highly popular and the number of actors increased. All of the theatres had a stable, state-funded budget. Again, however, the drawback was the heavy control imposed on them by the regime: censorship was ever-present and only ideologically-accepted plays were allowed. More progressive theatres managed to survive in some remote cities that became favorite destinations for young actors, but they generally had only a local audience.

Cinemas evolved the same way as the theatres; sometimes the same establishment served both purposes. Movies were very popular, and from the 1960s, foreign films started becoming quite widespread. Western films, when shown, were heavily censored: entire sections were cut, and dialogue was translated only using ideologically accepted words. Domestic or "friendly" foreign productions constituted the bulk of films in cinemas. During this period, cinematography started to develop in Romania and the first successful short films were made based on Caragiale's plays. Financed by the government, during the 1960s, a whole industry developed at Buftea, a town close to Bucharest, and some films, especially gangster, Western-genre, and historical movies were very well received by the public. The most prolific director was Sergiu Nicolaescu, and probably the most-acclaimed actor from that period was Amza Pellea.

In the same period create and publish one of the most important and creative Romanian pests from the last 60 years, Adrian Păunescu. Journalist at the Flacăra newspaper, founder of the cultural and social movement called Cenaclul Flacăra ( The Flame Cenacle) who promoted folk artists from all over the patriotism and the cultural values of our nation.

Prayer for parents

Enigmatically and tranquilly

While finishing their purpose

Beside us ... give up ... and die,

Our dearest, dearest parents.

God, please bring them back to us,

No matter how bad was their life,

And make them young as they once were,

Make them younger than we are.

For the ones who gave birth to us

Give an order ... Do something

To prolong their stay with us

Make them start over again.

They've paid with their life

for their sons' mistakes

God, give Eternal Life,

To our dying parents.

Behold them going away,

Behold them fading away,

Candles burning in a cuckoo's nest

As they ponder, as they snow.

Full of diseases and sufferings

All of us, are returning to the dust

As long as we are alive, as long as they are around ...

Honor and obey your parents.

The Earth is getting heavier

The departing is getting even harder

I kiss your hand, my father!

I kiss your hand, my mother!

But why are you looking at me like that

My daughter and my son?

I'll be the one to follow

My dear ones, I am leaving you as well.

I kiss your hand, my father!

I kiss your hand, my mother!

Farewell, my son!

Farewell, my daughter!

Oh my father, oh my son!

Oh my mother, oh my daughter!

Repeatable burden

Who has parents, on earth not in thought

He still hears even in sleep the eyes of the world crying

If we have been, if we have been not, or if we are good,

Today getting older we are missing the parents.

What parents? Some people who don’t have room anymore

By so many children and so much bad luck

Some crosses, alive yet, breathing harder and harder,

Are these parents who always sigh.

What parents? Some people, there they too,

Who painful know what is one hundred of lei bill.

Whether they are young or not, according their documents,

It doesn’t matter at all, they’ve become white of longing

To have their child a step higher,

How much more work, and what torment, what sleeplessness!

Even now, when I’m writing as if I’d scream,

I know and feel them, suffering somewhere.

We remember of them, after long weeks

Old children what we are, with old parents

If they bought woods, if their bones ache,

If they didn’t die sad in their houses…

Between them and children is a progeny of dogs,

And is the shadow of lead of the daily bread.

Who has parents, on earth, not in thought,

He still hears even in sleep the eyes of world crying.

That from all that exist, the hardest thing is to be,

Not a child of parents, but a parent of children.

The eyes of world weeping, many tears have been wept

But for the flood, is not yet enough.

Do we still have parents? Do they still have children?

On the land of crosses, only human not to be.

Humbled of needs and with bowed head,

In a poor little town, in a remote village,

They are still waiting even now, signs from ancestors,

Or letters from the children telling they are lucky,

And like some ghosts, they come rarely out at the gates,

Talking about us, as about their dead ancestors.

Who has parents, is not lost yet,

Who has parents still has a past.

They made us, they raised us, they brought us here,

Where we have our own children.

They can seem annoying , when you have nothing to ask them,

And generally they are bothering a bit.

They either don’t see, either don’t hear, either make the steps too small,

Either it takes too long time to tell them and explain,

Hunchbacks, bents, in an infernal rhythm,

They ask if you know a chief of a hospital.

Isn’t it that you feel a pity of all,

Especially that they can not anymore?

That you feel them as a burden and they know that it is true,

And they look at you like they’d implore you…

We still have, we have yet a short time to carry

On the conscience the burden of this decline

And then we’ll be very free under heaven,

They will be less those who don’t have and ask to us.

And when we’ll start to feel too

That a burden we are for our children,

And hardly after a sad and late time ,

When we’ll know desperately news which today they don’t know,

We’ll understand why the children soon forget,

And they don’t see any eye of the world crying,

And why is not flood on the surface,

Although always is raining, although eternally has snowed,

Although the world where we’ve become parents,

For an eternity is shaken of weeping.

Romanian Culture in exile during communist regime.

Romanians in exile

A consequence of the communist attitude towards the bourgeoisie elites in general, was the creation, for the first time in Romania's history, of a diaspora. Three individuals emerged as the most important Romanians abroad: playwright Eugen Ionescu (1909–1994) (who became known in France as Eugène Ionesco), creator of the Theatre of the Absurd and eventual member of the Académie française; religious historian and writer Mircea Eliade (1907–1986); and the essayist and philosopher Emil Cioran (1911–1996), the greatest French-writing master of style after Pascal. Fellow Romanian Ioan Petre Culianu continued Eliade's work with great success, in the United States.

Another member of the diaspora who distinguished himself was the philosopher and logician Stephane Lupasco. The communist rule in Romania, unlike most of the other countries of the Eastern bloc permanently repudiated the Romanians who had left their country and labeled them as traitors to the motherland. So, neither Mircea Eliade, nor Eugène Ionesco, nor Emil Cioran, whose works would be published in this country sporadically after 1960, could see their native land again. It was only after 1989 that the process of regaining the values of the diaspora and of reintegrating its personalities into this country's culture could be started seriously, a process marked in its turn by tension and disagreements.

Well-known Romanian musicians outside of Romania during this period include conductors Sergiu Celibidache—the main conductor at the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and later of Munich Philharmonic Orchestra—and Constantin Silvestri, main conductor at the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra. Gheorghe Zamfir was a virtuoso of the pan pipes and made this instrument known to a modern worldwide audience, and was also a composer or interpreter for a great number of movies. Composer and architect Iannis Xenakis was born in Romania and spent his childhood there.

George Emil Palade a cell biologist and a teacher became the first Romanian to receive the Nobel Prize, winning the 1974 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for describing the structure and function of organelles in cells. Elie Wiesel, who received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986, was born in the Romanian town of Sighetu Marmaţiei.

Evolution of the Romanian Culture after 1989

The fall of soviet-style communism in 1989 elated the cultural world, but the experience hasn't been an easy one due to problems in the transition period and the adoption of a free-market economy. The discontinuation of state and political control of culture brought about the long dreamt freedom of expression, but, at the same time, the state subsidies also stopped and Romania's culture was seriously affected by the side-effects of the incipient, still very imperfect, free-market economy and by inadequate material resources. Culture has had to cope with a variety of problems, one of them being a shift in people's interest in other areas such as the press and television. The search for a new cultural policy, relying on decentralization, seems to prevail now. People speak about a crisis of culture in this country, but if there is a crisis of culture, it is only at an institutional level.

After the fall of communism in 1989, there was an almost immediate explosion of publication of books previously censored by the regime. Books were published in huge numbers per edition, sales were high, and a great number of publishing houses appeared. However, this soon reached a saturation point, and publishing houses began to decline due to a combination of bad management, a rapid drop in sales, and the absence of subsidies. Many closed after publishing only a few titles; some changed their profile and started printing commercial literature - mainly translations - and the state-owned publishers entered a "state of lethargy". The latter survived due to state financing, but their publishing activity diminished. Despite this, some publishing houses managed to survive and develop by implementing market-oriented policies, and by improving the quality and overall appearance of the books they published. Among the most notable contemporary Romanian publishers are Humanitas in Bucharest, Polirom in Iaşi, and Teora, which specializes in technical topics and dictionaries. Some publishing houses developed their own chains or bookstores, and also other new, privately owned bookstore chains opened, replacing the old state-owned ones.

Culturally oriented newsprint periodicals followed a similar trajectory of boom and bust. A few have survived and managed to raise their quality and to maintain a critical spirit despite the hardships they encountered. Dilemma Veche (Old Dilemma) and Revista 22 (Magazine 22) remain respected forces in Romanian culture, with Observator Cultural a lesser, but also respected, weekly paper. Also, a state-financed radio (Radio România Cultural) and a television channel (TVR Cultural) with a cultural program exist, but they are not highly popular.

Many new young writers appeared, but due to financial constraints, only those who have gained a strong reputation could get the financial backing to publish their works. The Writers Association, which should, in principle, support these writers' efforts, hasn't undergone much change since 1989 and there is much controversy surrounding its activity and purpose. The most successful writers, like Mircea Cărtărescu, Horia-Roman Patapievici, Andrei Pleşu, Gabriel Liiceanu, and Mircea Dinescu, are respected personalities in Romanian life, but they have to devote some of their would-be writing time to other activities, mainly journalism. The ties with the Romanian diaspora are now very strong and even foreign-language Romanian writers like Andrei Codrescu (who now writes primarily in English) are very popular.

Romanian theatre also suffered from economic hardships, and its popularity decreased drastically due to the increased popularity of television and other entertainment channels. Some theatres survived due to their prestige (and some continued subsidies); others survived through good management, investing in themselves and earning a steady audience through the high quality of their productions. Experimental or independent theatres appeared and are quite popular in university cities. Uniter - The Romanian Theatres Association - gives yearly awards to the best performances. Some of the most critically acclaimed directors in contemporary Romania are Silviu Purcărete, Mihai Maniutiu, Tompa Gabor, Alexandru Dabija, and Alexandru Darie. Also, among the most appreciated actors, both from the new and old generation, one can name Ştefan Iordache, Victor Rebenciuc, Maia Morgenstern, Marcel Iureş, Horaţiu Mălăele, Ion Caramitru, Mircea Diaconu, Marius Chivu, and others.

Due to the lack of funds, Romanian film-making suffered heavily in the 1990s; even now, as of 2005, a lot of controversy surrounds state aid for movies. Well-known directors such as Dan Piţa and Lucian Pintilie have had a certain degree of continued success, and younger directors such as Nae Caranfil and Cristi Puiu have become highly respected. Caranfil's film Filantropica and Puiu's The Death of Mr. Lăzărescu were extremely well received and gained awards at international festivals in Paris and Cannes. Besides domestic production, Romania became a favorite destination for international producers due to the low cost of filming there, and big investments have been made in large studios.

The number of cultural events held yearly in Romania has increased over the past few years. Some sporadic events like the "2005 Bucharest CowParade" have been well received and yearly events and festivals have continually attracted interest. Medieval festivals held in cities in Transylvania, which combine street theatre with music and battle reenactments to create a very lively atmosphere, are some of the most popular events. In theatre, a yearly National Festival takes place, and one of the most important international theatre festivals is the "The Sibiu Theatre Festival", while in filmmaking, the "TIFF" Film Festival in Cluj, the "Dakino" Film Festival in Bucharest, and the "Anonimul" Film Festival in the Danube Delta have an even stronger international presence. In music, the most important event is the "George Enescu" Classical Music Festival but also festivals like "Jeunesses Musicales" International Festival and Jazz festivals in Sibiu and Bucharest are appreciated. An important event took place in 2007 when the city of Sibiu was, along with Luxembourg, the European Capital of Culture